The Joker is one of the most interesting characters in comics. He somehow positioned himself as the evil counterpart to Batman, despite there being no obvious connection between bats and clowns. Over the years he’s been a precision killer, a laughingstock, and a mass murderer. With so many stories featuring him from so many different perspectives, the quality of his villainy and stories often oscillates between great and terrible.

With that in mind, let’s take a look at the Joker’s history, how he became so iconic, and why I now try to avoid reading any stories he appears in.

Origins and Inspirations

Although Batman stories had been on shelves for about a year in the pages of Detective Comics, he didn’t get his own title until 1940, which coincides with the Joker’s first appearance. Batman #1 was originally intended to be the first and last appearance of the character. With a clown face inspired by Conrad Veidt’s role in the silent film The Man Who Laughs and a sense of theatrical macabre, he made an ideal foil for Batman.

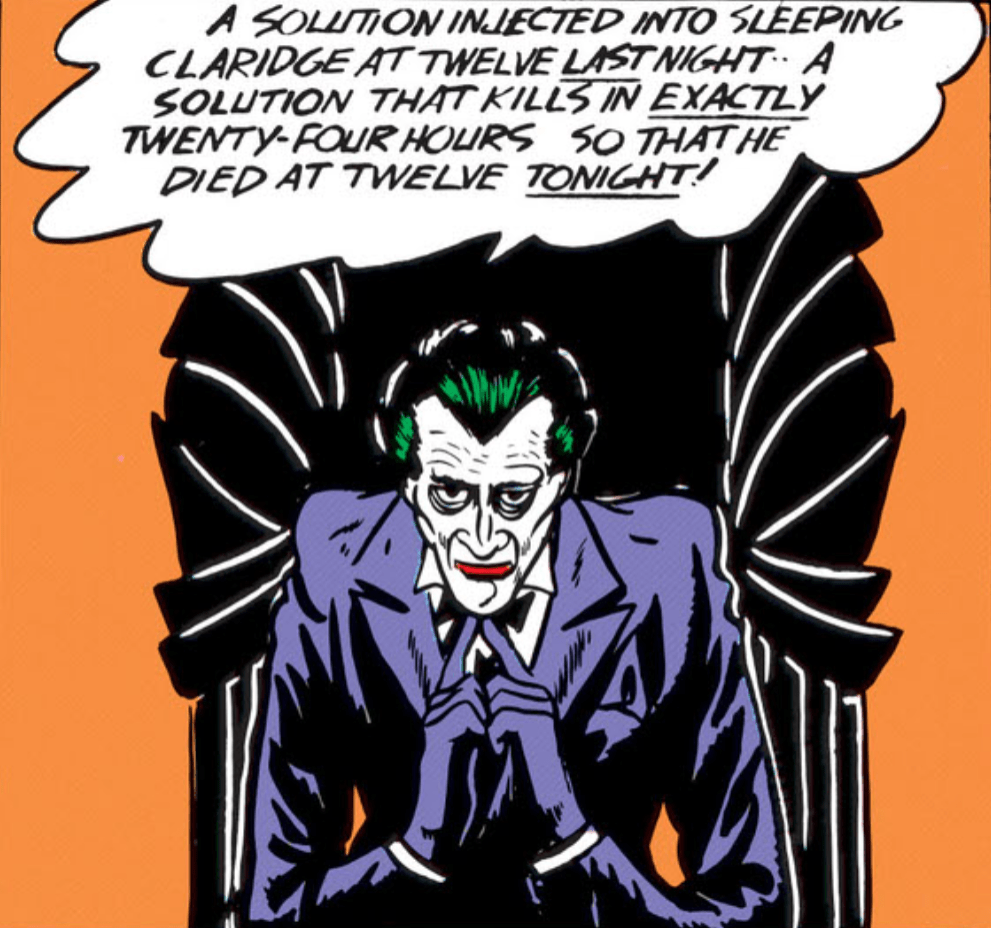

In the Joker’s first appearance, he wasn’t crazy; just evil. He had the trademark purple suit and clown face, but he didn’t tell jokes or indulge in his insanity. His name and motif seemed inspired by the playing card more than a comedian. A master of chemicals and poisons, he picked out high-profile individuals and told them what time they would die. Sure enough, those individuals dropped dead at the very time the Joker mentioned, even with the police protecting the victim and with Batman lurking outside. Upon their death, the victim’s face would contort into a hideous rictus grin, the result of a poison that would become one of the Joker’s trademarks.

The early Joker also managed to outfight Batman on more than one occasion. His combat prowess would disappear over the years as DC Comics decided to make Batman more and more superhuman by turning him into the best martial artist and strategical mind in the world. Batman wasn’t completely outdone by the Joker, however, and defeated him not once but twice in the same comic book during his first appearance. At the end of his second appearance, the Joker accidentally stabbed himself while lunging at Batman with a knife. This was supposed to be his death scene, but Editor Whitney Ellsworth had some amazing foresight and had a panel added to the comic that hinted that the Joker had survived. If it hadn’t been for that last minute addition, the most popular comic book villain ever might have died in relative obscurity.

The Man Who Laughs…and Does Little Else

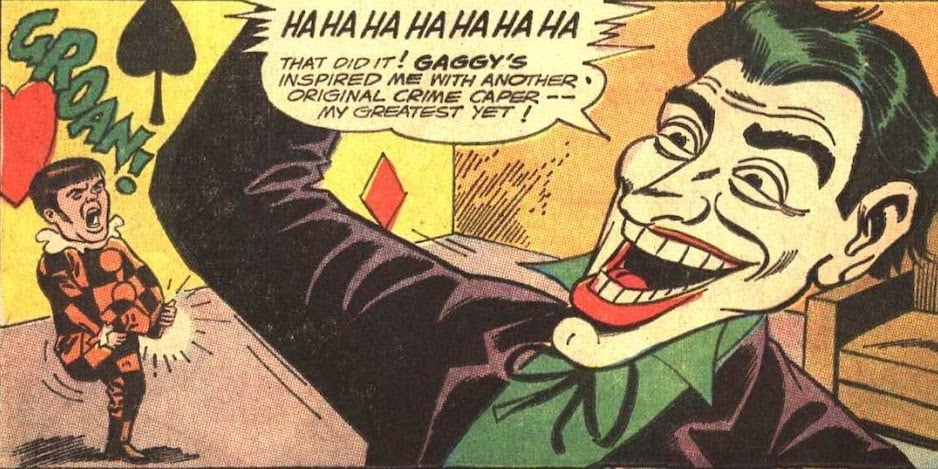

That early version of the Joker, with his sharply evil criminal mind and his surprising prowess in battle, disappeared fairly quickly. Comic books in general lost their popularity going into the 1950s. More damaging than that, though, was the fact that the government stepped in to take the teeth out of comic book storytelling. The Comics Code Authority began censoring comics, and mandated that all villains lose completely to heroes at the end of every story. Since the Joker looked like a clown, that’s what he became. He got more gadgets and his schemes grew grander but less dangerous. Ultimately, he focused more on the spectacle of his “jokes” rather than the actual crimes committed.

By the mid 1960s, the Joker disappeared almost entirely, except for Cesar Romero’s portrayal on the Batman television series.

Just in his first couple of decades of existence, the Joker demonstrates how a villain can be written impressively and then how he can be ruined. The original Joker did something few people could do: he matched the Batman stride for stride. While he was always ultimately defeated, he remained a menace that Batman had to pull out all the stops against. In the 50s and 60s, though, he became a buffoon who existed more for comic relief than anything else. A villain simply doesn’t have any teeth if he isn’t shown to be a match for the hero, which is why the character became stagnant very quickly.

Return to Villainy

Toward the end of the Silver Age, the Joker circled the drain of obscurity. Cesar Romero’s manic displays in the 1960s Batman TV series kept the character alive in the public consciousness, but he became less and less frequently used in the comics. But as the Bronze Age emerged in the 1970s, the Joker made a triumphant return.

By 1973, the Joker had been gone from comics for four years. He came back in the classic story “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge,” which synthesized the zany clown of the 60s with the homicidal maniac of the Golden Age. Case in point was when he gave one of his old henchmen an exploding cigar. The henchman, figuring that it was yet another one of the Joker’s corny gag, thought nothing of it until the explosive proved to be nitroglycerin.

The Joker presented in this story provided the template for years to come: he was still a prankster and a clown, but his insanity gave him a dangerous and unpredictable edge. One could never tell whether he was planning an elaborate joke or actually trying to commit a murder.

Another Bronze Age story, “The Laughing Fish,” punctuated how the Joker could function as both buffoon and villain. In that story, the Joker used a chemical to give all the fish in Gotham City his unique grin. He then demands a patent on the fish, hoping to get rich off the royalties. When the bureaucrats of Gotham have the gall to tell him that the law doesn’t work that way, he starts killing them one by one until Batman eventually stops him.

By the 1970s, Batman was well-defined as someone with a code and rules. The Golden Age Joker had been little more than another criminal foe, albeit a dangerous one. The Silver Age Joker focused so much on gags that he was effectively toothless. With a simple but effective twist, the Bronze Age created a villain who could prove an enduring nemesis for Batman: someone who not only lacked a code, but was so far removed from reality and decency that when he threw a pie nobody could know for sure whether it was made with whipped cream or cyanide.

A Much Darker Villain

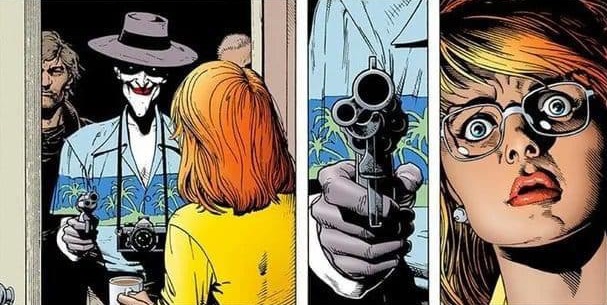

The 1980s brought two things to the Joker: multiple possible origins and some of the most personally villainous things he had done to date. The Killing Joke hit shelves in 1988, presenting a Joker who had been a failed standup comedian before a series of misfortunes drove him insane. The truth of this origin remained questionable, since the Joker himself admits that his memories of the events change often. Regardless, his most personal tale to date also brought visceral pain to Batman’s family when he shot and paralyzed Barbara Gordon, aka Batgirl.

Ironically, Barbara wasn’t shot in the line of duty or because the Joker knew she was Batgirl–she just happened to be close to her father, Commissioner Gordon. The Joker’s plan to use that pain to drive the Commissioner insane failed, but his penchant for crossing the line and hurting those closest to Batman was just beginning.

Later in 1988, the Joker crossed paths with Jason Todd, the second Robin, who had gone looking for his mother. Tragedy struck again, with the Joker capturing Robin, brutally beating him with a crowbar, and then blowing up the building he was in. Batman arrived to save him, but was too late.

Previously, even the more murderous versions of the Joker killed victims who were basically nameless, lacking a firm place in the Batman mythos. In 1988, all that changed and the Joker suddenly became someone who would brutalize the Bat-family with glee. Yet in an odd twist, both the wounding of Batgirl and the murder of Robin were incidental to the Joker’s larger plans. In the former case, he was trying to prove that Jim Gordon would snap under enough pressure. In the latter case, Robin just happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time while the Joker was hatching an unrelated plot.

The 1980s closed with Tim Burton’s Batman, the first real blockbuster superhero movie. This film gave the Joker another origin, presenting him as a gangster who fell into a vat of chemicals. It also tied him into Batman’s origin by having him be the gunman who killed Bruce Wayne’s parents.

It’s hard to say whether the juxtaposition of possible origins for the character and him becoming more personally vindictive are linked. One might argue that we get to know more about the Joker, his crimes have to become more personal to compensate.

Media Influences

The Joker has been portrayed by many actors over the years, with Cesar Romero being particularly influential in that he kept the character from fading into obscurity during the 1960s. The 1990s and 2000s saw a pair of very influential performances in animation and live action which shaped the Joker’s personality for a generation or more.

Batman: the Animated Series came out in 1992 and loosely followed the continuity of the Tim Burton-directed Batman and Batman Returns. Mark Hamill came in as a last-minute replacement for Tim Curry and became the iconic voice of the Joker, to the point where he is still in demand to this day despite having retired from the role several times by now. Hamill’s Joker showcased the duality of the character, to the point where one could never tell what was a joke and what was a murderous plot. As an example, in “Christmas with the Joker,” he seemingly puts hundreds of lives at risk for the sole purpose of hitting Batman in the face with a pie. Meanwhile, in Batman Beyond: Return of the Joker, he executes a plot that drives Robin insane and almost gets Batman to commit murder.

On the flip side, Heath Ledger’s Oscar-winning performance as the Joker in 2008’s The Dark Knight presented something closer to the Golden Age version of the character. This Joker didn’t have time for expensive props and elaborate gags, instead wearing the clown makeup as a sort of mockery of society’s rules. Despite being a very different take on the character than what the comics had shown before, the quality of the film and of Ledger’s performance gained immediate traction. The Brave and the Bold (volume 3) #31 even presented a scene from The Dark Knight as part of the Joker’s memories.

As so often happens, the comics latched onto a popular presentation of a character in cinema and overcompensated in their attempt to bring that style to the page. If people liked Heath Ledger’s darker Joker from The Dark Knight, they were about to get an overdose on the “serious” version of the clown.

Face Off

DC rebooted its continuity in 2011, and the first Joker story featured him paying a visit to a villain called the Dollmaker for a very peculiar surgical procedure: he had his face cut off.

The reason for this disfiguration was never explained, and nothing really got done with it. The Joker eventually recovered the skin peeled off his face and strapped it back on, wearing it like a mask. Maybe DC had a plan for that and just didn’t follow through with it, or maybe they were just going for sheer shock value to drum up hype for their (ultimately failed) relaunch.

Regardless, this face removal lasted for about three years before his classic look was restored in 2014’s “Endgame.” That story ended with the apparent deaths of both Batman and the Joker, but they both got better. Nobody ever really mentioned the face thing or did anything with it.

And speaking of weird plot twists that nobody did anything with…

The Three Jokers

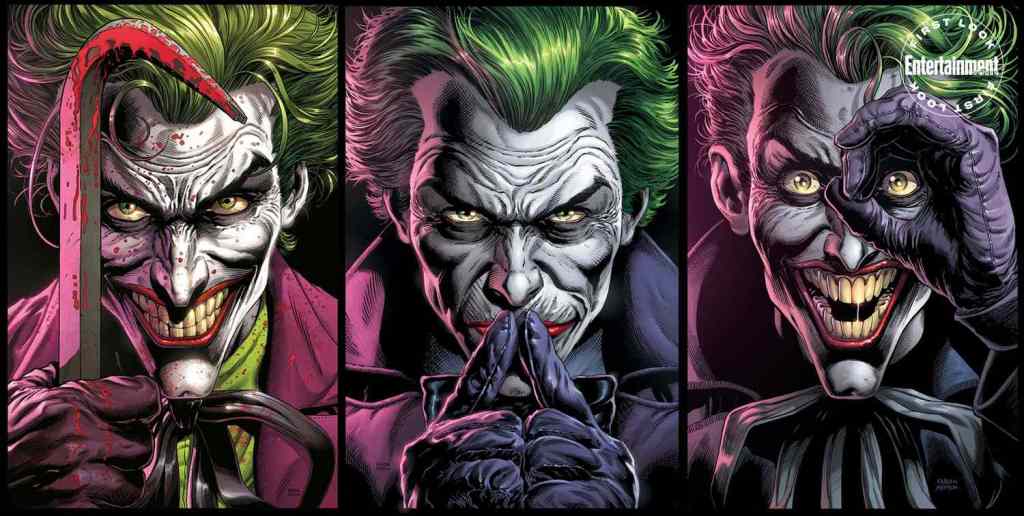

During the “Darkseid War” storyline, Batman learned something very disturbing when he sought knowledge about the Joker’s true identity: there were actually three of them.

The follow-up story “Three Jokers,” didn’t come out until half a decade later–another example of DC trying to do something new with the character but not seeming to have a clear plan of action.

In “Three Jokers,” writer Geoff Johns presented an explanation for the Joker’s radical changes in mood over the years: he was three separate people, all donning the Joker identity. There was the cunning Golden Age version who rarely smiled, the buffoonish Silver Age version who cared more about punchlines than violence, and the modern-day Joker who had killed Jason Todd and crippled Barbara Gordon, among other atrocities.

“Three Jokers” ultimately ends with a resurrected Jason killing the Silver Age version and the modern Joker killing the Golden Age version. Meanwhile, Batman seemingly confirms the origin story originally told in “The Killing Joke,” where the modern Joker was a failed comedian who was pressured into crime before being doused with chemicals–and that Joker’s wife and child are still alive but in witness protection.

Confused? If you are, don’t worry. “Three Jokers” was printed under DC’s Black Label, which is generally considered non-canon. Series artist Jason Fabok has stated that it is not in continuity, indicating that there are certain things they couldn’t have done if it were canon. On the other hand, it has been referenced since, so the verdict is…I guess it’s as canon as you want to make it.

That is, in a way, fitting with the Joker. Even the story revealing his “true” identity might be a joke of sorts on the reader.

The Joker has been all over the place, and it really seems at times that modern writers don’t know what to do with him. After the brutal but iconic actions he took in the 80s, the character has sort of spun his wheels, always remaining a big threat but lacking the pure shock of those classic tales. The only thing we know for sure about the character is that he’ll show up to make Batman’s life miserable again in the future, whether the joke is funny or not.

Images: DC Comics