Wizards of the Coast still claims that the new Dungeons & Dragons rulebooks released in time with the game’s 50th anniversary is still part of the game’s 5th edition, but that number is really just a marketing decision. The game has really undergone at least ten different edition changes across two brand names. That doesn’t include optional rulebooks that, if incorporated, radically changed the way the game played.

So what edition are we really on? Here’s my subjective scorecard on the many faces of D&D.

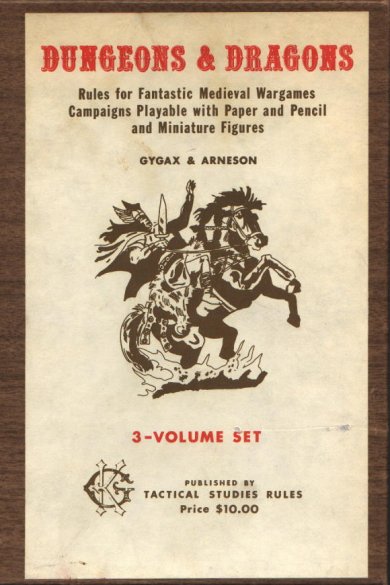

1974: Dungeons & Dragons

This is the original “brown box” release of the game, also known as “0e.” It was also later re-released in a white box; when folks mention brown box or white box D&D, they’re usually talking about this edition.

It had a 1,000 copy print run to start with, which sold out with remarkable speed. The core concepts of D&D got introduced here. Your character had six ability scores, one of four races (human, elf, dwarf, or hobbit), and one of three classes (fighting-man, cleric, or magic-user). Legal troubles with the Tolkien estate caused later printings to change certain elements cribbed from The Lord of the Rings. Hobbits became halflings, balrogs became balors, and ents became treants.

These rules were very broadly drawn and sometimes contradictory, allowing a lot of room for interpretation. When people cite the “old school” philosophy of coming up with house rules willy-nilly, they’re referring to a style of play that was necessary due to the many gaps in said rules. In fact, the game relied on other, sometimes competing, products to fill in its gaps. The brown box relied on TSR’s miniatures game Chainmail for its combat rules and Avalon Hill’s Outdoor Survival for wilderness rules.

Four supplements later expanded the rules to make the game fit a framework that fans know today. Greyhawk gave us the thief class, spells up to 9th level, and allowed weapons to deal variable damage (previously all weapons did 1d6 damage, 1d6+1 for fighting-men). Blackmoor introduced the monk and assassin and also had some ill-fated critical hit tables. Eldritch Wizardry introduced the druid, demons, and psionics. Gods, Demi-Gods, and Heroes was the most controversial supplement, as it introduced stats for various mythological creatures, allowing powergamers to kill Zeus if they wanted to.

The original D&D was messy but innovative. It was designed to let miniature wargamers do something new with their games. Nobody foresaw the hit it would become, and the game grew rapidly and chaotically as a result.

1978: Dungeons & Dragons Basic Rules

The basic set penned by J. Eric Holmes occupies an odd place in D&D history. It was a revision of the original 1974 set, but it also came out at a time when Advanced Dungeons & Dragons was becoming a thing. (The Monster Manual had come out in 1977, but the game’s three core books wouldn’t be fully released until the Dungeon Masters Guide came out in 1979.)

The first of many basic sets for the game, the Holmes boxed set included rules for the first three levels of play, using the same races and classes from the 1974 edition, although the fighting-man had become the fighter and the thief was now a core class. It has some idiosyncrasies that keep it from being compatible with any other edition of D&D, including a five-tiered alignment system. Originally, you could be lawful, neutral, or chaotic. This set’s alignment system allowed you to be lawful, neutral, chaotic, good, or evil. By the time AD&D was finally finished, the nine-tiered alignment system that allowed for combinations like chaotic good had become the standard.

Although this version of the game didn’t have support beyond 3rd level, it did include suggestions on continuing play. This very much jived with D&D‘s “these are guidelines, you make the real rules” mindset of the 1970s.

The Holmes basic set is an oddity due to its place in D&D history, but it provided a good starting point for new players and made the game more comprehensible after multiple supplements had caused the 1974 version to become bloated.

1979: Advanced Dungeons & Dragons

When people say “1st edition,” they usually mean this game. It was the third iteration of Dungeons & Dragons, but the first one bearing the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons brand. With deeper rules and more support, AD&D would remain the more popular version of the game for years.

1st edition AD&D was essentially original D&D with all the supplements included and even more added. The game used three hardcover books instead of a boxed set like before, and eventually expanded to having about a dozen hard-cover supplements that introduced optional items like drow, the cavalier class, non-weapon proficiencies, and even a seventh ability score, Comeliness.

While AD&D added a ton of new options, it failed in its attempts to standardize D&D, thanks to some bizarre rules. For example, each weapon had certain bonuses or penalties that made them more effective against certain types of armor. The initiative system was also mind-boggling, causing a lot of people to toss it aside for a set of house rules.

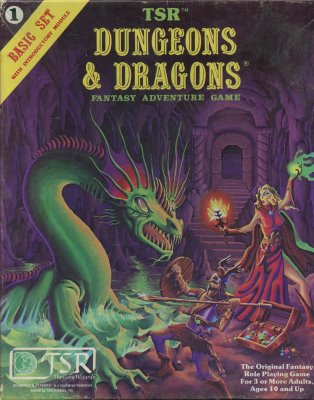

1981: Dungeons & Dragons Basic and Expert Sets

A split between D&D co-creators Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax also led to a schism within the brand itself. Gygax created argued that AD&D was a different game than D&D and that he therefore did not need to pay royalties to Arneson, a matter that the latter sued over. Meanwhile, perhaps to reinforce the idea that AD&D wasn’t just a continuation of D&D, two new boxed sets carrying the Dungeons & Dragons (no A) brand came out.

Crafted by Tom Moldvay and featuring cover art by Erol Otus, the Basic Set and Expert Set covered levels 1-3 and 4-14, respectively, giving players a chance to play with simpler rules than AD&D offered over a full campaign.

This version of D&D retained some elements from the 1974 system (and AD&D) while also simplifying some systems. Initiative was simply a d6 roll to see who went first, and alignment options went back to lawful, neutral, and chaotic. You didn’t choose a race – you were assumed to be human unless you chose the elf, dwarf, or halfling class, which combined racial features and class features into one. Some choices seemed arbitrary and might have been made so Gygax could justify his legal claim that the game was different than AD&D, such as the base Armor Class being 9 instead of 10.

I would argue that this set is probably the best implementation of 20th century D&D, albeit without the array of options that made AD&D so much more popular.

1983: Dungeons & Dragons Basic, Expert, Companion, Master, and Immortal Rules

To add another wrinkle to the struggle for control of the D&D brand, the 1981 D&D set was largely crafted without oversight from Gary Gygax. He would try to rectify that fact by having Frank Mentzer redo D&D just two years later. The 1983 edition contained most of the standard features of its predecessor, including the races-as-classes rule. However, the basic set was targeted toward someone who had no idea what a role-playing game was. You learned the rules through a pair of solo adventures before trying them out with a group. This set showed up on the shelves of big stores like Toys R Us, making it a true mass market success.

Following the previous pattern, the Basic Set had rules for levels 1-3, with an Expert Set providing rules for levels 4-14. From there, though, the game went in some very new directions. The Companion Set included rules for levels 15-25 with a focus on kingdom building and world-shattering quests. Then the Master Set took players from levels 26-36, dealing with extraplanar threats and the quest for immortality. Finally, the game totally changed with the Immortal Set, which allowed players to continue their adventures as god-like beings.

These rules were re-released several times, including the 1991 The New, Easy to Master Dungeons & Dragons Game which served as my introduction to D&D and the 1994 Classic Dungeons & Dragons set. The Basic, Master, Companion, and Expert sets were all consolidated in the 1991 Rules Cyclopedia, which still stands as the only one-volume set of rules that allowed you to play the full D&D game (unless you wanted to play gods, in which case the immortals rules were translated over to the Wrath of the Immortals boxed set).

The BECMI edition of the game cleaned up some details of the previous Basic and Expert sets, but then expanded it in crazy directions. This led to some clunkiness in later sets, but you could take the off-ramp at any point you wanted by just not buying the next set.

1989: Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 2nd Edition

It wasn’t until the game was 15 years old until it had an “official” edition change. Gary Gygax had begun pondering a new edition at least as early as 1985, but an internal power struggle at TSR forced him out before such a thing could come to fruition. Instead, the new version of the AD&D game occurred under the watch of new CEO Lorraine Williams, with profound tonal changes in addition to rules alterations.

The rules got largely polished, with many changes that gamers had wanted to see for years such as improved initiative rules, higher level limits, and more. But D&D had also come under fire by parent groups concerned about the game’s questionable content, and the new edition made some sweeping changes to appease those groups. Half-orcs disappeared as a core race, although they would return later, the assassin class was removed, and demons and devils were renamed tanar’ri and baatezu.

Ironically, while one stated goal was to initially make the game more manageable than the dozen rule books of 1st edition, 2nd edition suffered from massive rules bloat, expanding to dozens or possibly even hundreds of supplemental rulebooks. The quality of the books varied wildly, and many modules references supposedly optional materials as necessary.

Nonetheless, 2nd edition was a more polished rules set compared to 1st edition. Moreover, while the explosion of campaign settings during the 1990s was a terrible business idea, it proved great creatively, giving fans interesting new worlds to explore through product lines like Planescape, Dark Sun, Al-Qadim, and much more.

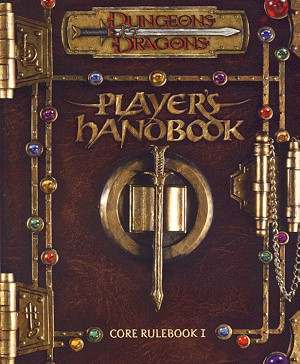

2000: Dungeons & Dragons 3rd Edition

If they wanted to be accurate, Wizards of the Coast could have named this version of the game 7th edition. In truth, however, it should have been called AD&D 3rd edition, since it is a descendant of that line rather than the simpler D&D line. For marketing and licensing reasons, however, the new owners of the D&D trademark decided that it would be best to keep only one brand name rather than confusing people with two similar but incompatible systems.

Third edition was a huge departure from its predecessors, redesigning the system from the ground up to make it streamlined and intuitive. Everything now revolved around a d20 roll to determine success. THAC0 was eliminated, higher ACs were better than lower ones, and there were only three saving throws. Class and level limits were gone, and each race and class was balanced against the others.

The game still had a lot of complexity–in fact, many would argue that 3rd edition was the most complex version to date. However, many parts of the game were more intuitive. As an example, an introductory adventure in the BECMI days suggested that avoiding falling into a pit required a saving throw against Dragon Breath, which was arguable at best. In the new edition, it was clearly a Reflex save, since it required the use of agility and dexterity. Many other areas of the old rules that were foggy in their adjudication were made more intuitive, even if the overall complexity of the game increased.

With Lorraine Williams gone and Wizards of the Coast no longer worried about the moral guardians who had troubled TSR in the 1990s, 3rd edition reincorporated some elements that had been partially purged before. Half-orcs returned as a core race, demons and devils were back in the Monster Manual, and so on. This won back some old fans, while the modernized rules set brought in new players.

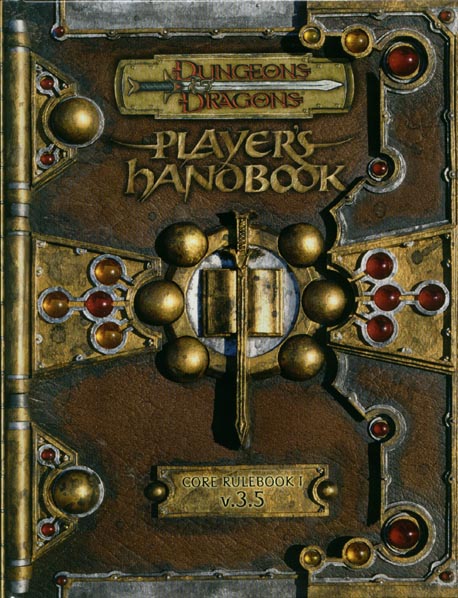

2003: Dungeons & Dragons 3.5 Edition

While D&D 3rd edition was a success, the supplementary material didn’t sell nearly as well as the core books. Moreover, the plan all along had apparently been to release a revised edition about halfway through the game’s lifespan. Three years seems like a short time to let an edition stand on its own, but that’s all the original 3rd edition got before Wizards of the Coast released the “3.5” edition.

This version, billed as a “half edition,” was still different enough from what came before that previous books needed errata. Classes got rebalanced, the skill list got an overhaul, spells got tweaked, and more. The designers also made sure to make the battle mat and miniatures the standard style of running a combat, going so far as to include a battle mat in the back of the Dungeon Master’s Guide.

Some of the changes were legitimate improvements over 3rd edition. Rangers were a useful class again, epic level rules became available in the core books, and players got more feats, spells, and options. On the other hand, three years was a very short time to wait before asking everyone to re-buy their core books, and 3.5 didn’t come at the generously discounted pricing that the original 3rd edition books debuted at.

2008: Dungeons & Dragons 4th Edition

Fourth edition D&D is, in my opinion, the result of two things.

First, the designers of the game overreacted to online criticism. There was a lot of vitriol against 3rd edition in the 2000s, and forums that now have a “no edition warring” policy instead became battlegrounds for very long and protracted battles where folks would nitpick or defend virtually every aspect of the game. Negativity broadcasts farther than positivity, and I think the designers felt a lot of pressure to “fix” the game.

At the same time, Hasbro wanted more money out of a brand that had generally done middling numbers. They looked at the extremely popular World of Warcraft and wondered why D&D couldn’t sell like that. The game’s art style changed to resemble World of Warcraft, the rules focused more on tactical combat, and the folks behind the edition change intended to fully integrate digital tools.

In short, 4th edition was designed to capture a wholly new audience.

That’s not to say that 4th edition didn’t also try to appeal to long-time players, or that it broke entirely with the traditions of D&D. But it changed a lot of the core assumptions of the game. The core races and classes were torn into, introducing some newbies like dragonborn to the Player’s Handbook while tossing half-orcs, gnomes, and druids, among others, into supplemental material. Rather than just the spellcasters having magic, every class got something like spells, be it combat maneuvers, special feats, or so on. The core mythology was also overhauled, as designers tore apart the “Great Wheel” planar system in favor of an “Astral Sea” where the planes were effectively islands waiting to be explored.

The crux of 4th edition’s design was Dungeons & Dragons Insider, a suite of digital tools designed to make the game easy to play. Wizards of the Coast had huge plans for that platform, even killing the print versions of Dragon and Dungeon magazines so they could be integrated as extras that subscribers got online. Many things might have been, but a shocking murder-suicide derailed development. That tragedy ensured that Dungeons & Dragons Insider would never deliver on the full list of promises made at the launch of 4th edition.

Just a few years into this edition, Wizards of the Coast released a quasi-revision called Dungeons & Dragons Essentials. I don’t like these rules as a new edition because they kept the same core found in the Player’s Handbook, but repackaged them in a different format with new class options and monsters. The options available to players changed, but the rules of the game remained the same, so in my opinion D&D Essentials does not constitute its own edition (as opposed to 3.5, which changed enough rules that you couldn’t play the game using a 3.0 Player’s Handbook).

Fourth edition had high hopes, but it became the most divisive edition to date. While some loved how well it delivered on its promise of tactical depth and a re-envisioning of some troublesome D&D tropes, others felt like it changed too much in an attempt to chase a new audience that ultimately never jumped on board.

2014: Dungeons & Dragons 5th Edition

After the last 4th edition product hit the shelves in 2012, D&D went into a sort of hibernation. Wizards of the Coast unrolled “D&D Next,” a playtest for the next edition that included numerous surveys targeted not so much toward feedback on the rules but rather feedback on whether particular components of the game felt like D&D. Ultimately, 5th edition rolled out to wild success, bringing back many people who had abandoned the game and propelling D&D to new heights.

Early on, 5th edition got a reputation for being “rules light,” a description that only fits it in comparison to the previous few editions of the game. Compared to actual rules light RPGs, 5th edition is still clunky. However, the game emphasized a more natural language and beginner-friendly tone than either 3rd or 4th edition had taken. Even though the balance was out of whack in several areas (most notably, spellcasters remained far more dominant in the late game than martial-focused characters), the designers managed to get the feel just right to appeal to a huge mass audience.

Fifth edition also benefited from being in the right place at the right time. It came about just as live-play podcasts were getting big, and the juggernaut Critical Role switched from Pathfinder to D&D as they changed formats. The COVID-19 pandemic saw a huge surge in remote gaming, which 5th edition benefited from partly due to its mammoth profile in the RPG industry.

While sales numbers are hard to come by, there’s no doubt that 5th edition sold better than anything since at least the 80s, and may have even eclipsed 1st edition AD&D and the old BECMI sets in terms of profit. Whether the rules are to your liking or not, 5th edition D&D definitely put the game back on the map.

2024: Dungeons & Dragons 2024

For marketing reasons, Wizards of the Coast is loathe to say they’re changing editions, but they are. Releasing on the year that D&D celebrates its 50th anniversary, this version of the game uses the chassis of 5th edition but has some pretty sweeping changes, from ability score modifiers being decoupled from race (now called species) to feats no longer being optional to tweaks to classes, monsters, and spells.

Wizards of the Coast maintains that this version of the game is still 5th edition, but it has as many tweaks to it as 2nd edition AD&D or D&D 3.5 had. Despite the changes, though, it seems that D&D has finally settled back into a base system they like, and switching between 5th edition and the new 2024 edition is about on par with bringing 1st edition AD&D material into 2nd edition. It took a major shakeup in the industry and the collapse of TSR to radically alter the game back in 2000, so I think it’s safe to say that modern D&D will look more or less like what came out in 2014 until a major event or collapse of the brand forces a reimagining of the game.

Will the 2024 edition harness the success that D&D hit upon in 2014? Will having to buy new books prove divisive to fans? We’ll have to wait and see.