With its incredibly deep game play and commitment for Forgotten Realms lore (even when I wish they would ignore said lore), Baldur’s Gate 3 is a triumph for the Dungeons & Dragons franchise. More than any other computer game I’ve ever played, it feels like I’m playing a tabletop game with the production values of a Hollywood blockbuster.

But the game’s predecessors are no slouches, either. In fact, for the past 25 years, Baldur’s Gate 1 and Baldur’s Gate 2 have been unicorns that other RPGs chased. While other D&D games have strengths of their own, none quite replicated the deep and massive story of those old games while also maintaining a distinctly D&D feel.

Yet those older games, despite making Baldur’s Gate 3 possible, feel very different from the newest iteration of the franchise. Some of that is merely a matter of scope and funding; Baldur’s Gate 1 and 2 came out in older days with less technological power and far less money behind them. But a lot of it has to do with the fact that Dungeons & Dragons has changed dramatically over the years. The original used the 2nd edition rules, while Baldur’s Gate 3 uses 5th edition as its base. The rules have changed, but so have the types of stories fans want to see.

Rolling for Ability Scores

When you fired up the character creation screen in the original Baldur’s Gate game, you picked out your gender, race, and class. After that, a couple of proficiencies and a decision about what color skin, hair, and clothing you had were the final decision points before you began the prologue. Except, of course, for ability scores.

The game randomly generated your character’s ability scores, but allowed you to reassign points as desired and reroll if you wanted. Speaking for myself and everyone else I know who played the game, that meant 20+ minutes or re-rolling to try to get about 85-90 points to distribute between the six ability scores. The disparity between a decent score and a great one was huge; a fighter with a Strength of 14 gained no noticeable advantage, but one with an 18/99 Strength score got +2 to hit and +5 damage on all attacks, making the game lots easier. Simialrly, a mage could run with a 14 Intelligence score, but you weren’t likely to have much success learning new spells if you didn’t have an 18 (60% chance to learn versus 85% chance, and if you failed to learn from a scroll, that scroll was destroyed).

Baldur’s Gate 3 leaves ability score determination until the last step, but eschews with rolling entirely. The game relies on point buy instead, allowing players to customize scores but keeping everyone on more or less even ground while still allowing some space to cater to the min-maxers. You aren’t likely to start with a weaker than average character, but you also aren’t going to wind up with a super character to start with, either.

On the surface, the normalization of ability scores takes some of the random fun out of character creation. Anyone who owned a 2nd edition Player’s Handbook likely remembers a full page of the ability scores chapter dedicated to how interesting it can be to play a character with low scores. In practice, however, the game was heavily skewed toward characters who started with an 18 in their prime abilities. Your 12 Wisdom cleric might have been fun, but it certainly sucked having a 5% chance of spell failure while your 18 Wisdom counterpart had no risk of failure and multiple bonus spells per day.

Of course, the randomness in ability scores was one of the main ways to customize your character back then. In the original Baldur’s Gate, you didn’t even craft a backstory for your character; you always began as a sheltered 20-year-old who lived in Candlekeep. Come Baldur’s Gate 3, a long and weird backstory seems to be mandatory for main characters…

This Group is Full of Weirdos!

The original Baldur’s Gate games had a pretty wide disparity in terms of character backgrounds. For every Aerie (an avariel whose wings had been cut off by slavers, who was adopted by a gnome, and served as an innocent yet powerful spellcaster for the local circus before joining your group), there was a Korgan (a really bloodthirsty dwarf).

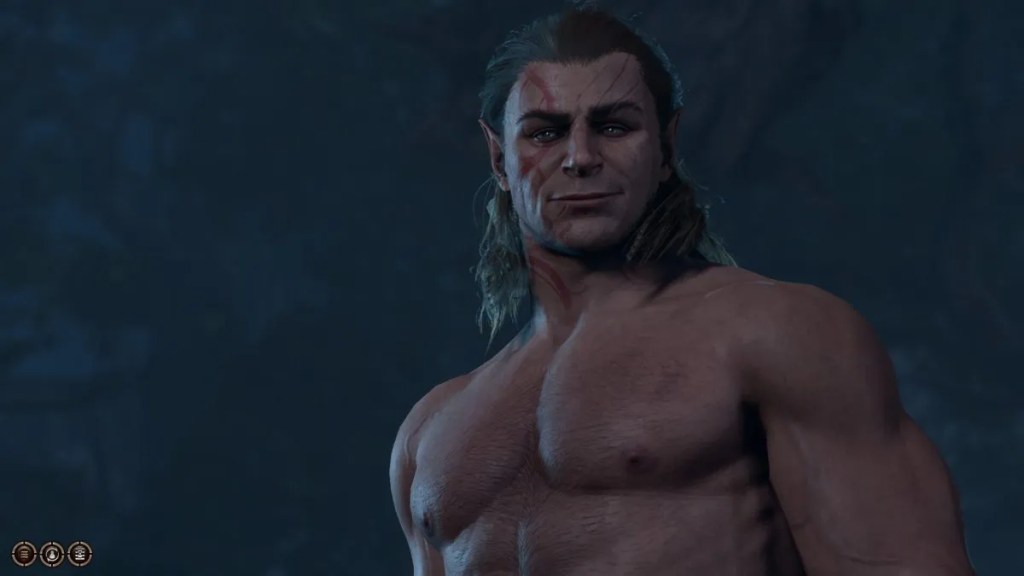

This pretty well reflected the way AD&D worked; some folks loved deep backstories for their characters, and others saw “dwarf fighter” as a full concept. That divide still exists in modern gaming, but a lot of folks have been introduced to the hobby through streams like Critical Role which have helped really popularize the more Aerie-like concepts. Baldur’s Gate 3 takes that philosophy and rolls with it, resulting in a party that…well, I’ll let Astarion say it:

The characters in your party include such colorful personas as a vampire who was effectively a prostitute for his master for 200 years, a woman with a badly-maintained engine in place of her heart, and a wizard who walks the world as the spurned lover of the goddess of magic. That’s not touching upon the Dark Urge origin, which allows you to play an amnesiac with murderous tendencies and a fiendish butler who tries to get you to indulge them.

There is a place for the simple concepts in Baldur’s Gate 3 parties, but they’re not at the forefront of the game. You could easily play a custom PC who is defined by their race and class, and you could even go with hirelings instead of the default companions, creating a group of bread-and-butter adventurers who find themselves thrust into a bizarre situation. The option exists, but it is not the default assumption.

D&D arose from war games, where units died all the time, and old games featured plenty of character death. As such, you didn’t often need to come up with a detailed concept, because who wants to spend two hours writing a backstory if your PC dies in 30 minutes? As the editions have marched on, increased odds of character survival and adventures that focus more on the narrative than combat and exploration have become commonplace. Baldur’s Gate 3 reflects that with its delightfully bizarre cast of characters.

Gameplay and Story Segregation

Once upon a time, D&D used the game rules to represent the physics of the setting. In some cases, it was pretty straightforward; your Dexterity score measured how agile you were relative to others, for examples. In other areas, it required more stretching. Things like alignment languages or the reason why spellcasters forgot their spell as soon as they cast it got many varied in-world explanations, many receiving mixed reactions from fans.

There is still some of that in 5th edition and Baldur’s Gate 3, but there are many areas where the game is very happy to turn a blind eye to the system mechanics in order to make the story work. For example, we have a big bear of an elven druid named Halsin. He’s a brawny hulk in appearance and has a Strength score of…10, because Strength isn’t a big mechanical need for druids.

Such decisions are part of game balance, since all the main characters have the same stat array. Giving Halsin an 18 Strength would mean taking away from more important druid stats, like Wisdom. By comparison, had Halsin shown up in Baldur’s Gate 2 he might have had a Strength of 17 to go with a Wisdom of 16 and nobody would have batted an eye; those old characters weren’t balanced in that way.

Baldur’s Gate 3 also glosses over the fact that everyone starts at 1st level pretty quickly. Your group includes someone who has spent a decade fighting demons, a warlock who summons fiends, a wizard who used to be the chosen of the goddess of magic, but they all begin at 1st level. In-story, this is a result of the mind flayer tadpoles messing with your mind, but that explanation is the thinnest of wallpaper to explain away the fact that D&D doesn’t work as well if you start the campaign at level 10.

None of this is bad, but it would cause system shock to a gamer used to the old AD&D way of doing things…game mechanics aren’t physics anymore, and modern players don’t seem to mind the drift between gameplay and story like they used to.

Time Marches On

What might a hypothetical Baldur’s Gate 4 look like? It’s hard to say. The 25-year gap between the first and third game in the series reveals an interesting dichotomy, where characters have become more mechanically in-depth but the story is also more willing to occasionally toss out the rules to facilitate a cinematic story. I think a lot of this is caused by the influence of streaming shows like Critical Role, but who’s to say that they might still be guiding these trends in 2030?

Regardless of when it happens or what D&D edition it emulates, it is certain that an eventual Baldur’s Gate 4 will reflect a continuing evolution of role-playing games.